A Detour at Intel

1983-1984Greg Bryant

I played a tiny part during a key moment that arbitrarily and slightly shifted the direction of a vast movement, a torrent that transformed the world for the worse. Although it doesn't need to be, computing has been regressive, as has most advanced technology. This is because it provides leverage for power and greed, which stimulates wanton accumulation, inequality, and destruction. Many engineers notice this social problem, but they think "that's the way things are". And the technical work is typically too tempting, too remunerative, and (more rarely) too interesting, to refuse.

From below, it's easy to observe the willful ignorance of 'our great captains of industry'. They are completely indoctrinated and blinded by capitalist and technocratic ideology, and they're increasingly well-rewarded for the initiatives they take within this framework. They don't see it this way, of course, but operationally, they are sociopaths.

But a little about me: I was hired to work at Intel headquarters in 1983. How to describe this place? A high-tech, anti-union pillar of the United States' industrial hegemony. An anti-human, profit-driven, immoral tyranny, like all large corporations. I can't say enough bad things about the very existence of this category of human institution, which is built on the belief that gathering power, achieving monopoly, maintaining advantage, and prioritizing growth are somehow moral imperatives, along with a commitment to the harshest means to these ends: intense, wasteful, bullying competition, funded by a deceived public.

Sorry, that wasn't really about me. So, I was recruited as an experienced UNIX guru, with microprocessor expertise, quick on my feet, with many ideas.

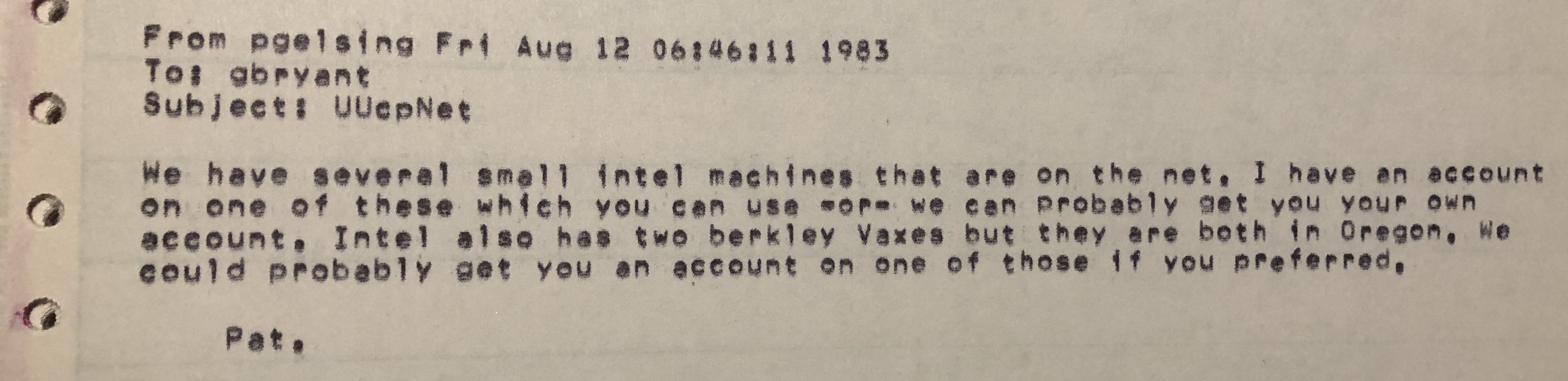

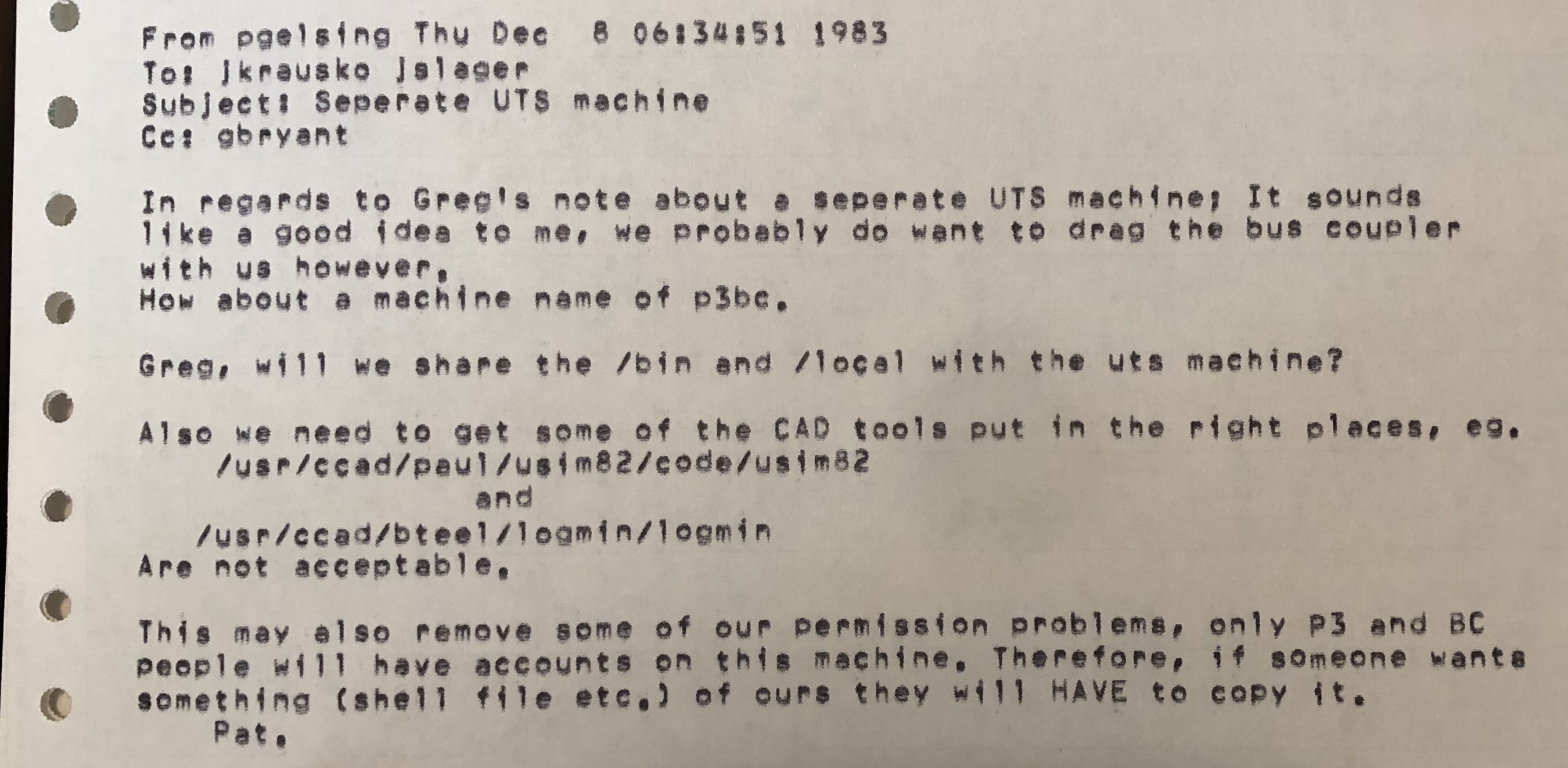

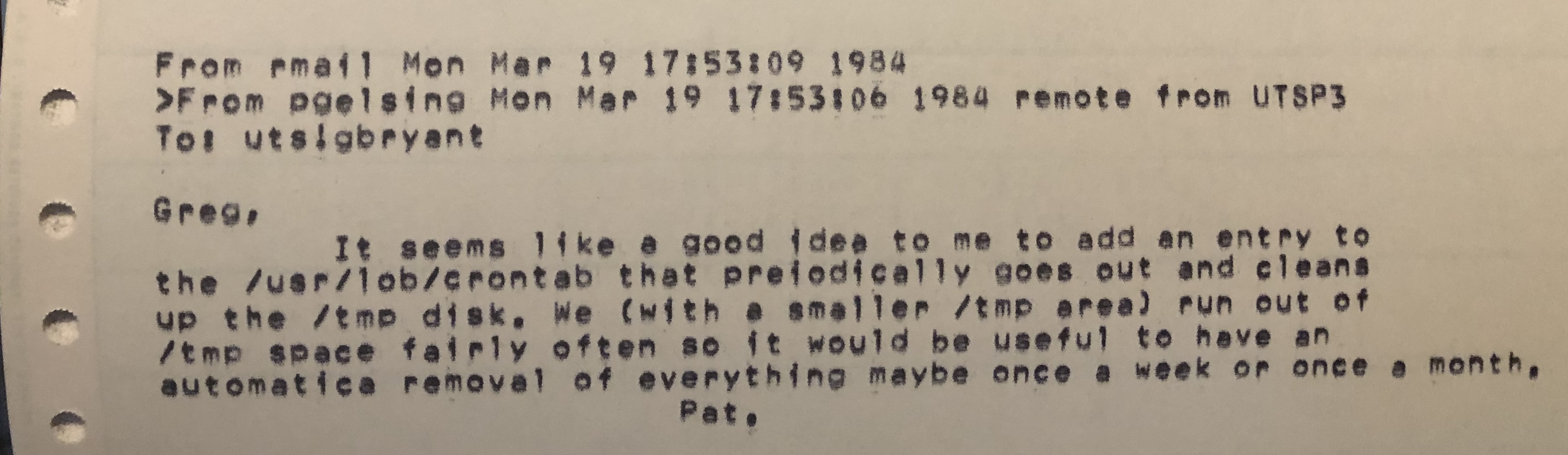

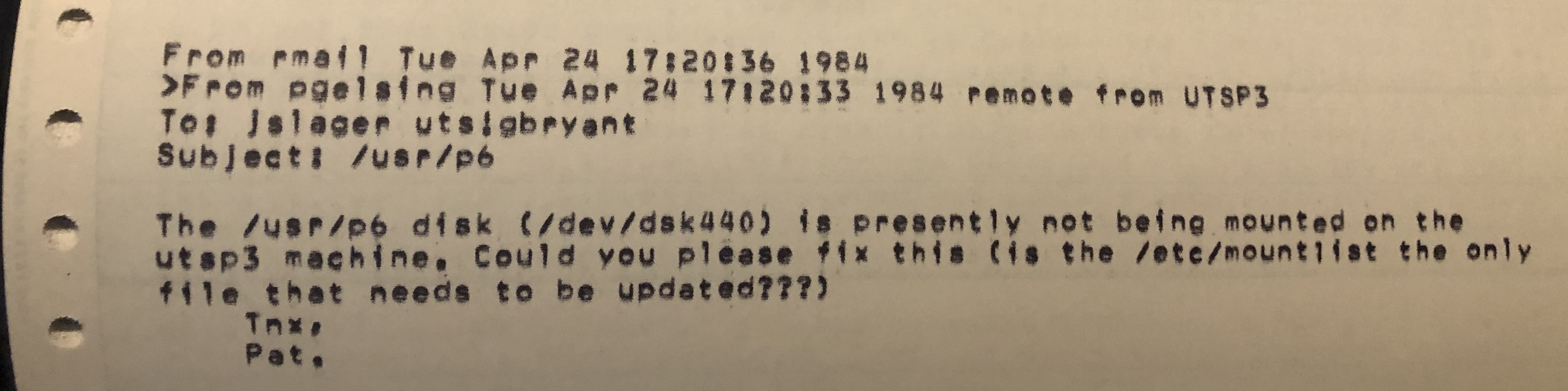

What was I supposed to do at Intel's HQ? Officially, my large remit was to technically support the corporate-wide migration to UNIX. But, in reality I was there to take the UNIX hacking load off a young Pat Gelsinger -- an increasingly important problem-solver, who needed time to get a VLSI engineering degree. My hiring was approved by a sharp and, in the end, successful, insurgent group at the global headquarters in Santa Clara. Like many insurgents, they had supporters among the oppressed at Intel, and some secret comrades up the management ladder. Ultimately, they had full establishment support when they were proving right. We were absolutely certain that microprocessor engineering needed to be treated as software engineering ... the p3 or 386 or 80386 or i386 in fact could not have been built without UNIX and its software tools.

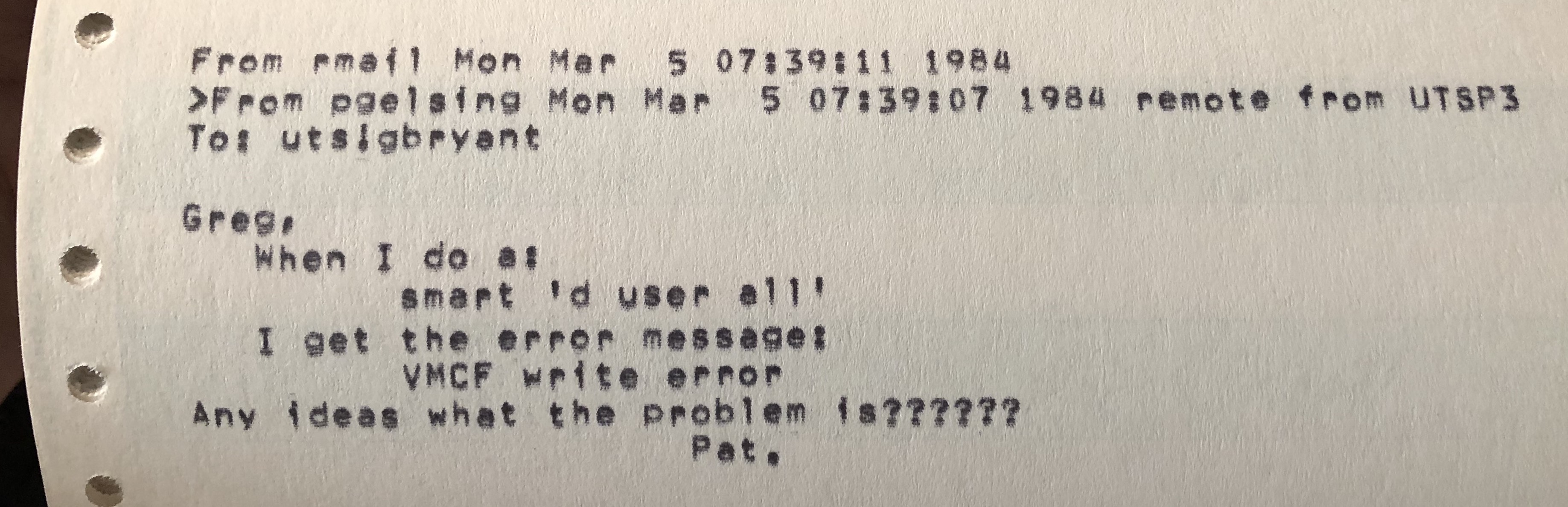

(This is indirectly self-referential, because Gelsinger's book on the 80386 was the primary inspiration for the second major free OS based on unix (the first was BSD): Linux. Here's an overhead presentation by Pat Gelsinger in early 1984 on UNIX, or the version we were licensing: Amdahl's UTS, which I maintained on a single VM within an IBM 3081. The presentation summarizes the material we collaborated on, in the preceding months).

This insurgency, and other tempests in a teapot, took place mostly on the top floor of a small, extremely ugly, two-story building. The battles had world-changing consequences only because of the vast monies and energies focused on this particular engine, Intel, which produced raw power for the computer industry. The executives who founded Intel were not influential because they were brilliant. They were clever when they wanted to be, but that's beside the point. They were successful because they'd been seduced by 'the drive to win', and took advantage of opportunities to grow their portfolios of technology, power, and finance. They built armies to serve the establishment. They happily helped to grow and support the empire, no matter the cost to the world. They sucked up the brightest people and nature's precious resources for power and profit, which they justified with convenient collective delusions of human progress. They weren't the only ones deluded in this way, of course. The 20th and 21st centuries unleashed a torrent of uninhibited tech daddies, a fate I managed to turn away from, but whose temptations I felt quite distinctly. If one looked at life in a totally selfish light, becoming a tech plutocrat seems like the only liberation available, in a world of alienation produced by extreme capitalism which, at that point, had already been extreme for a hundred years. Today, everyone is becoming aware that unchecked financial and industrial growth has burned the planet, and impoverished nearly everyone.

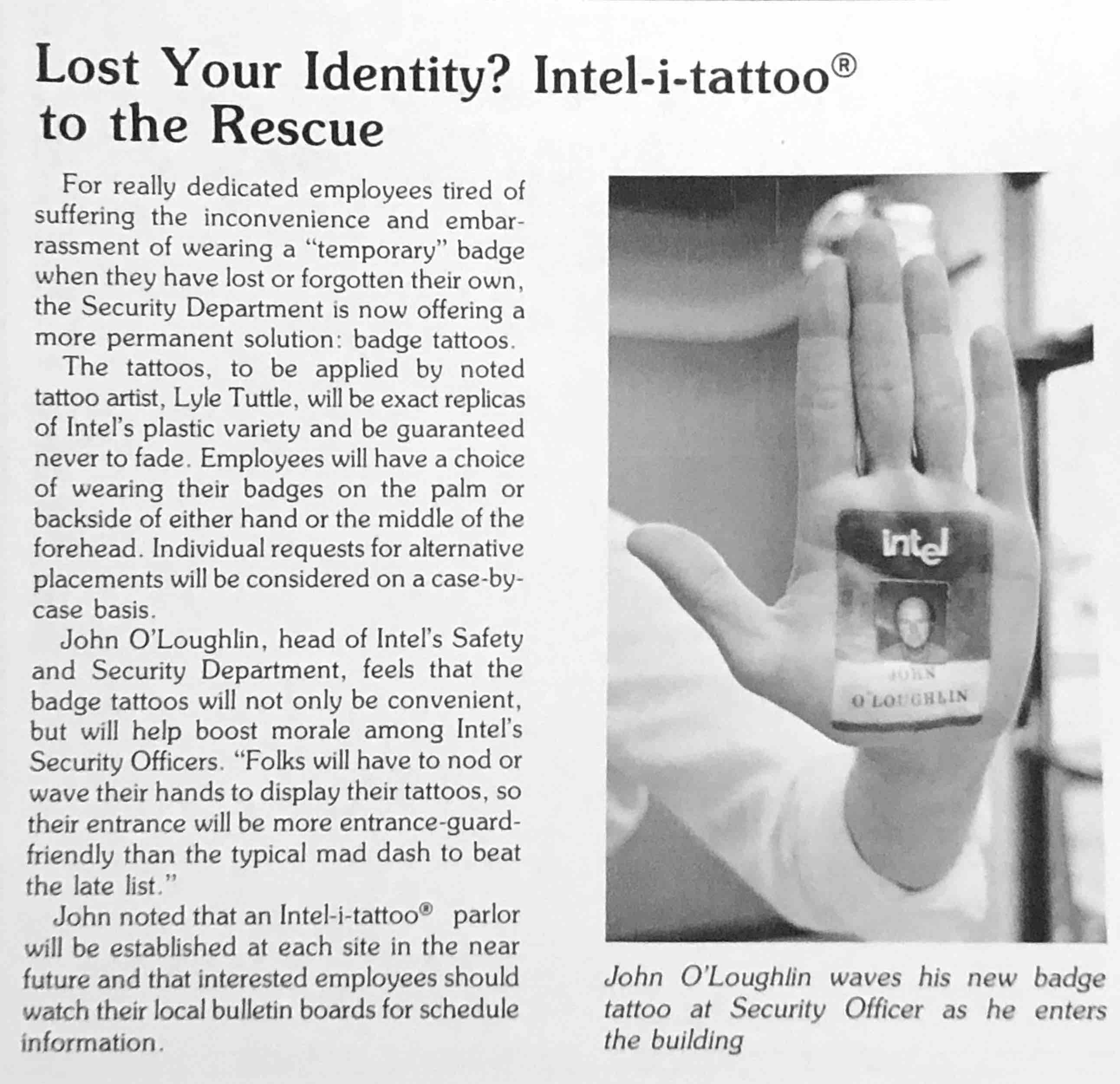

Gordon Moore, famous for observing the exact pace of this destruction, was the CEO, and he would stalk the floor restlessly. He'd regularly pull a mildly displeased face at me, for purposefully not wearing my badge ... but he would not tell me to wear it. At that point, he wasn't completely sure if badges were sufficiently important to lose a good engineer over. After all, I thought: everyone knew me -- why would I need a badge? He once sat down next to me in the cafeteria, and started chatting about someone who had left intel recently, and how easily people moved from company to company, and how that was his history too, and how that was simply 'the way of the valley' (this was my first job south of San Francisco) -- a kind of rebellion, later to be known as 'disruption'. I think he was trying to tacitly acknowledge the value of my rebellion against the badges, but gently encourage me to wear one, without saying so explicitly. Of course, I didn't. Sometime after I quit intel, this kind of tolerance would completely disappear.

Everyone at Intel was working unecessarily hard, and typically on busy-work, despite the popular "work smarter, not harder" slogan. I found myself rebelling against this obvious dissonance, and would take ever-longer lunch breaks offsite. The employees suffocated in an impossibly bureaucratic, autocratic, and sterile office-political atmosphere. It was managerial, hierarchical, irrational, primitive, and dull. Not only were unions forbidden: co-operation, even for the good of the company, needed to be approved -- and so became covert instead. Executives often think their organizational management regulations are responsible for work getting done, but the opposite is true: there is a natural, basic communal ethic that makes up the shortfall whenever it's clear that executives are clueless about what needs to be accomplished. It's a shame that people don't organize themselves into bottom-up decision-making structures more often. It would be much more effective, efficient, and adapted to real needs. People in power are, of course, very against that sort of thing.

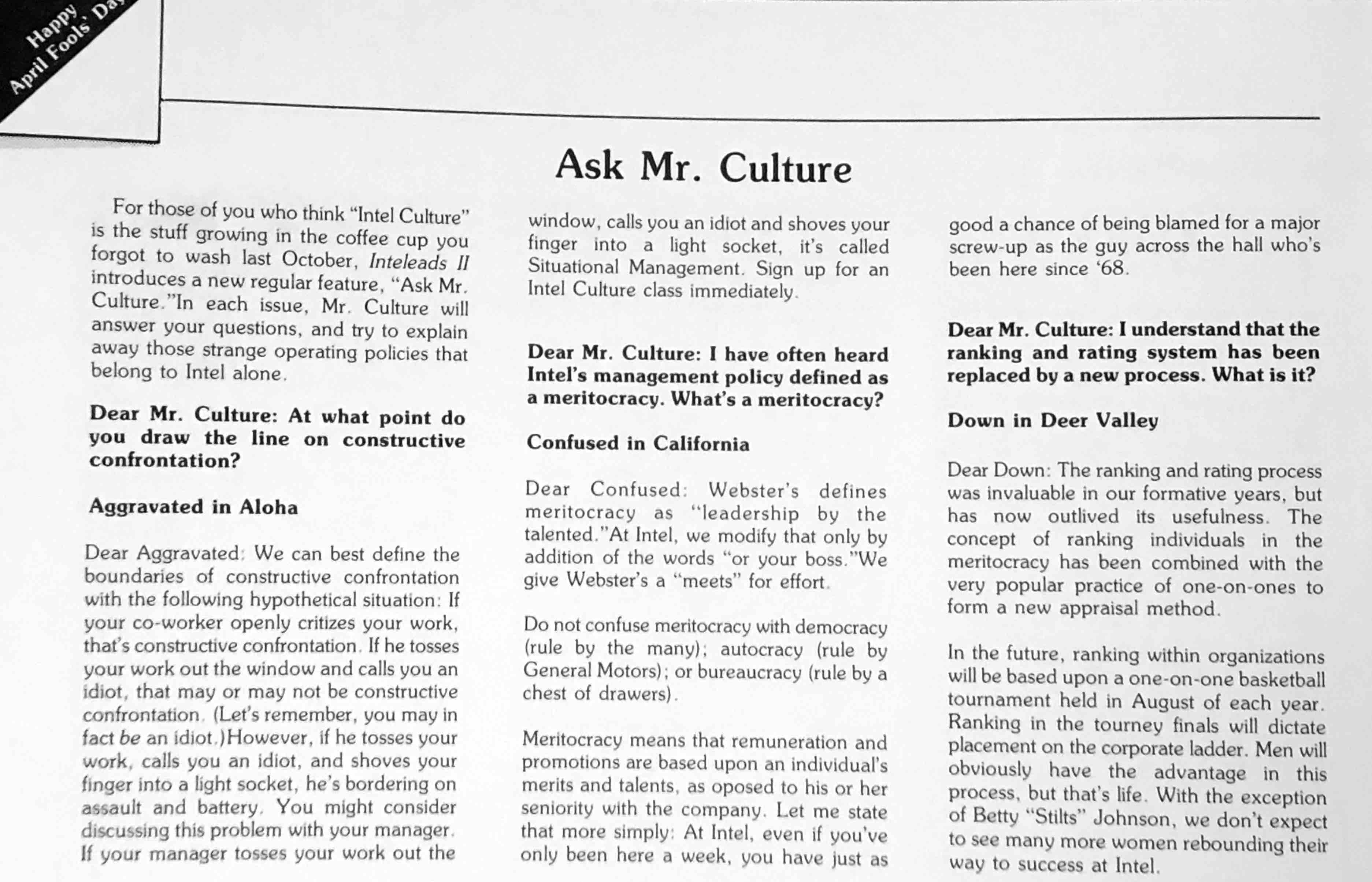

Intel had a patronizing, soul-sucking internal marketing campaign to teach everyone 'the' so-called 'Intel Culture', which seemed to mean that creativity, innovation, opportunity, mutual aid, social responsibility, and quality-of-life needed to be stifled at every turn.

Some of my immediate co-workers agreed with that assessment: the secret rebel group. But the engineering challenges were motivating, and consumed our attention. We enriched this new approach to producing microprocessors, while stitching together computing power to do the work. Again, the 80386 wouldn't have been buildable without UNIX -- itself a covert project, within Bell Labs from which the transistor also emerged -- as well as countless notions imported into electronic engineering from the world of software. The work we decided to take on in this airless environment (smoking was allowed, so this is a visceral memory for me) required tireless, diligent reasoning, systems-level rationality, and relentless bug-killing. I offered ideas, made observations, and sometimes debated, alongside another 'intel culture' affront: a nauseatingly unproductive and unsubtle divide-and-conquer mechanism, promulgated by the executive management, known as 'constructive confrontation'. Which (as the running joke went) was only confrontational, and never constructive. Still, it wasn't hard to win arguments, because we were borrowing successful general software principles and deploying them for the first time to complex chip design. All of that is laudable, but most of MY time at Intel was spent working with Gelsinger and others to cobble together a custom heterogenous network of real and virtual unix machines to improve our computing capacity and performance, to move the 386 or 'p3' project forward:

Although there were certainly brilliant people at Intel, the insanity of the organization itself drove me crazy by osmosis. I resigned in the middle of an additional storm of stupidity, this time from the outside, when IBM decided that 32-bit computers (including the 386) were overpowered for desktop machines ... and so they wouldn't be using the chip in their PCs at all! I still remember increasingly resenting IBM: (1) using these idiotic IBM DOS machines (tin cans compared to a similarly priced, far more sophisticated UNIX machines); (2) these hilariously uninteractive IBM 3270 terminals, which felt like keypunch machines, which forced you to fill a buffer and then explicitly send it away; and (3) the IBM 3081 itself -- gigantic, inflexible, outdated. That and the fact that Bill Gates was so strongly associated with IBM at the time, and was already clearly the agressively sociopathic capitalist that he's proven to be since, made me want to cover-up the IBM logo anywhere I saw it. Many others inside and outside Intel also saw no merit in the microprocessor group's hard work on facilitating backwards-compatibility for software, trying to make life easier for everyone. We forcefully advocated for it using arguments from the interoperability headaches that arose in the unix world (I was a C portability consultant prior to this job, and I was traumatized by incompatible hardware advancements). But these simple ideas were barely on the radar of establishment executives (and many still forget their importance today).

After over a year of these useless battles in the world's dullest environment, I gave my notice. Desperate, Pat Gelsinger and three senior rebels took me out to lunch.

In the tradition of Intel's 'renegades' they begged me to start a super-rational company -- building 32-bit machines with the 386 (after it was released) which could run all known software in virtual mode -- and then hire the 386 engineers away from Intel! They referred to various discussions we'd had during my time there, including the need to reject corporate propaganda and the big business mindset, and deprecate technologies that survived only because they were proprietary. (The free software of the past -- and hopefully of the future -- was part of this discussion. There was a moment, because of BSD, that AT&T, IBM, and Microsoft's importance looked vulnerable. Many people wanted to avoid the property-obsessed monopolistic insanity of people like Bill Gates. DOS and later Windows -- and the pre-unix Mac OS too -- were great examples of bad operating systems that became dominant because of money and power but not quality. The computer world, as most people have noticed, has a real quality problem, and seems to avoid the effort to make the right things, and make them work right, for people.)

But, deep down, they just thought I'd be a fun CEO, because I don't believe that anyone should indulge the fantasy that they can 'manage people'. Instead, people must work together to manage the project, and if possible, decide what the project is. Because that's what happens in successful projects anyway. Management is deluded if they think otherwise. It's better to clear away the chains of autocracy and get on with cooperative action.

But, I asked them: Why help Intel out of its stupor? Why take advantage of an obtuse IBM? Why promulgate computing at all? It's a dirty business, making chips and machines, despite its PR-cultivated post-industrial image. We were all fighting within the industry, but we weren't fighting to stop its problems! Is that doing the right thing? We fought out of frustration, and a sense of injustice, because we were at the bottom, and the people at the bottom know better than the people at the top. We were drawn to the technical problem of forcing 'business people', and even former engineers like our executives, to understand reality. But was that worthwhile? It depends on the situation, of course, and we need to force open these internal discussions. But I was so numb from Intel that I didn't feel anything in computing deserved that commitment and activism.

I also told them that, based on the examples I'd seen, I would become a worse person if I became a CEO.

So I said no.

So, they all stayed at Intel, and fought. Compaq decided to seize the opportunity -- or risk -- on the 386. The rebel project I'd helped for over a year ultimately became the most influential computer chip in history: the 80386, or i386, the microprocessor inspired by unix software practices.

And, after an exit and return, Pat Gelsinger is CEO of Intel now [2024 edit: no longer].